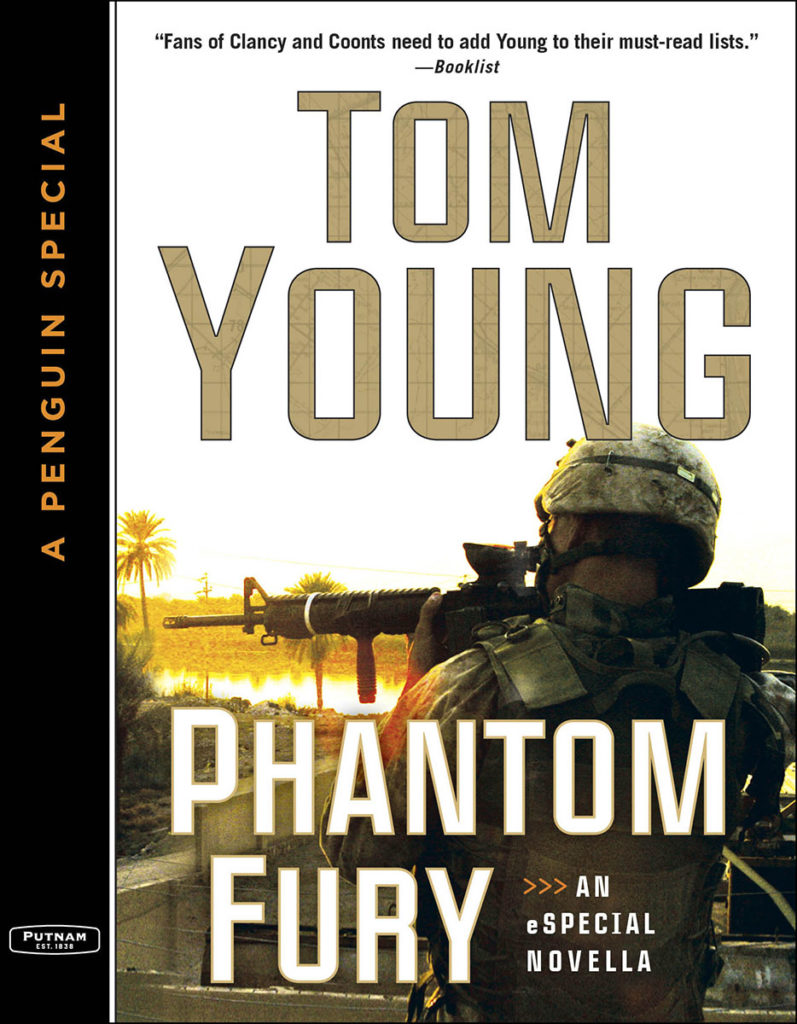

Phantom Fury

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble

Buy the Book: Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & NoblePublished by: Putnam Adult

Release Date: June 10, 2014

ISBN13: B00INIYH28

Overview

In Tom Young’s novel Sand and Fire, a six-foot-eight black Marine gunnery sergeant named A.E. Blount teams up with Young’s series heroes Michael Parson and Sophia Gold to fight an extraordinary terrorist in North Africa.

But it was a decade earlier, during Operation Phantom Fury in Fallujah, that Staff Sergeant Blount really learned what war meant. In this remarkable novella, riveting in its action, shocking in its candor, we see through his eyes as Blount and his comrades discover that the limits of what men will do, both for good and evil, go beyond anything they ever imagined; that the line between friend and enemy is much more complicated than they thought — and that courage and mercy come in the most surprising of forms.

Backstory: The Story Behind Phantom Fury

The Second Battle of Fallujah, in November 2004, embroiled U.S. Marines in some of the most intense urban combat of the Iraq War. By then, the forces of Saddam Hussein’s regime had collapsed, and the conflict had entered a phase of insurgency. Baathist hardliners and foreign fighters had turned Fallujah into a terrorist stronghold and hideout of insurgent leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.

At a cost of more than fifty American lives, Coalition forces took control of Fallujah by the middle of November. Historians estimate insurgent deaths at more than a thousand; an official tally does not exist. Al-Zarqawi escaped capture only to die in a U.S. air strike in 2006.

This story is a work of fiction. The Iraqi interpreter described in these pages is not based on any real person, living or dead. However, many of the details in this story come from firsthand accounts. Sadly, that includes the descriptions of victims tortured and killed by insurgents. Real-life events informed the chapter where Blount’s platoon finds a “torture studio,” as well as the scene where Marines discover a mosque used as a weapons cache. Other scenes taken from actual events include the shot-up amusement park, the air cover from the AC-130 gunship, and the Patriot Detail at the Air Force Theater Hospital in Balad. (The hospital’s Trauma Bay II remains on exhibit at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Silver Spring, Maryland.)

At the time of the Fallujah battle, I had recently finished a year and a half of active duty as a flight engineer with my West Virginia Air National Guard unit, and I had returned to my civilian job as an airline pilot. At the airline, I found myself reunited with several other pilots who had made it home safely from tours in Iraq. As we swapped stories, I learned that some of them—especially those who flew helicopters in the Guard or Reserve—had lost friends and suffered deep psychological wounds. One night, while training to regain currency in the airline’s jets, I shared a simulator cockpit with a pilot who had served eighteen years in the Army. During a break in the sim training, he told me he needed only two more years of Reserve duty to qualify for retirement pay. But he was getting out. He had seen more than his share of combat, and he’d had enough.

My unit, the 167th Airlift Wing, continued to support the war effort with missions in Iraq and the U.S. The stateside missions involved staging our C-130 transports at Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington, D.C. As Walter Reed Army Medical Center and the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda released recuperating troops, my squadron mates would fly them to their home bases.

Some of the patients were Marines wounded in Fallujah. To this day, my buddies speak reverently about the grit and courage of those men. In many cases, high-ranking Marine officers would meet the aircraft to honor their wounded and help carry them off the plane. These young warriors had given more to their country in a matter of days than most Americans will give in a lifetime—and many of them wanted nothing more than to heal quickly and rejoin their units.

This story is dedicated to them: the U.S. Marines who took Fallujah from terrorists and gave it back—at least for a while—to the civilians who lived there.

Excerpt

Chapter One

TO: Captain Anderson Sheehan

FROM: Staff Sergeant A. E. Blount

RE: After-action report, Operation Phantom Fury (8 November 2004)

UNCLASSIFIED/FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY

Sir,

You asked me to summarize the actions of First Platoon during the Second Battle of Fallujah, and to describe what we found in that house. To give you information for your report, the best I know to do is tell you everything I can remember in the order it happened. I don’t really like to think about the day we searched that house, but I’ll try to provide a factual account when I come to that part. To help the intel folks who might read this and didn’t go through the School of Infantry, I’ll explain the tactics when I need to.

Our interpreter, Mohammed al-Duri, joined us right before we moved into the town. We called him Snoop Dogg. Some of the guys said he looked like the rapper because he was skinny and had that same kind of mustache and goatee. I thought that was a stretch, but we had to call him something because we didn’t use his real name out loud. Couldn’t risk the wrong people knowing his identity. Snoop even wore a camo bandanna over his face most of the time so the insurgents couldn’t get a good look at him.